A’AGA something to be talked about or told

October 5, 2018

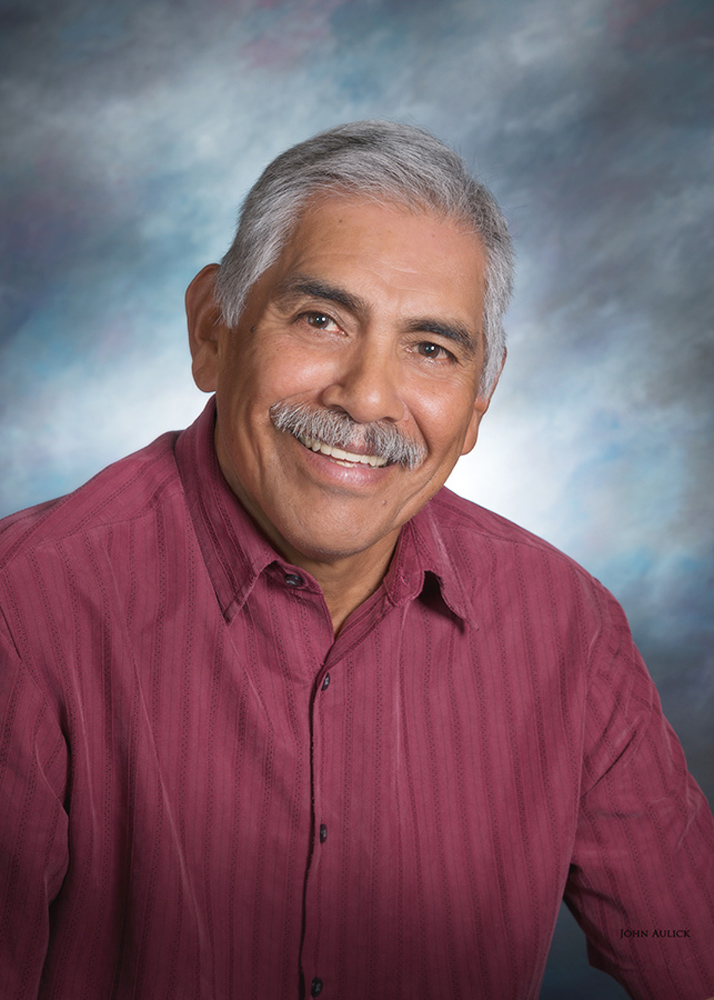

Billy Allen

Traveling through our community, some might wonder about the traditional, historical villages. Traditions and culture change – so, it would depend which time period (the Hohokam, the Spanish, American or twenty years ago), that someone wants information about. Can you imagine what people may have said when the first O’otham rode a horse INTO the village? “That’s not traditional! Who do you think are?” But it sure beat walking. Native cultures have always accepted changes. Today we avoid famine, talk English, and ride in steel horses (with air on full blast). Many of us make a good living because the “guardians” of our himdag adapted to new and better way of doing things.

With that written, let’s examine where our ancestors settled according to historical documents. I was loaned a copy of From Hohokam to O’odham, The Protohistoric Occupation of the Middle Gila River Valley, and Central Arizona by E. Christian Wells and am sharing what I learned. “Traditional” villages moved up and down along the river in an effort to find better water sources, food and for protection. Village elders who were seldom questioned usually made the travel decisions. However, families were not bound to obey, and were free to move or stay. But many hands make light work and there is safety in numbers, so the entire village usually migrated.

Four major settlement areas in which our villages moved in our early history were identified: Sacaton, Sweetwater, Casa Blanca, and the Pima Butte (Aji) areas. In the Sacaton area, a village called Tusonimo or La Encarnación existed in the 1700s. However Apache raids may have forced people to move to Sweetwater and Casa Blanca for safety. A Piipaash village existed in the area from about 1840 but was abandoned by 1870. Then beginning in about the 1850s, American facilities being built here such as a stagecoach stop, trading post, a school, and an Indian Agent’s home in Sacaton drew people from many different places into the area. Sacaton became the commercial and administrative center we know today. (Makes me think of that great baseball movie: “If you build it, they will come.”)

The Sweetwater area had several large villages dated from the 1700s. More than one early Spanish explorer mentions a large village called Uturituc or corner in this area. In 1914, Charles Southworth was placed in charge of identifying early irrigation areas along the Gila River. Apachoes, an O’otham who lived all his life in the Sweetwater area, told Mr. Southworth this village was called “hur-churl-jurk”. It meant a bare or open place by itself. In the early 1800s, Stotonick became the big village, as the result of O’otham tribal and military alliances dating from roughly 1697 to 1846. The alliance has been labeled as the Pima-Maricopa Confederation. Sweetwater village also appears in the 1800s and still exists.

The Casa Blanca area is a large area near the center of our current reservation. The area also experienced population growth due to Apache raids. Villages were forced to relocate to the southern bank of the akimel as villages moved closer together. Sratuka (full, will be known as Wetcamp) moved to the south bank but still farmed their fields on the north bank. Prior to 1850, Casa Blanca was the commercial and administrative center. In the early 1900s, the name Va’aki appears and refers to the mound of dirt left from the remains of an ancient building in the district. Earlier documents labeled this area La Tierra Amontonada (Earth Piled Up). It was also known as Tubus Cabors (Jeved Kavuddk or Earth Hill).

In studying the Sacate (a Spanish term for good grass feed) area it shows a continuous area of occupation extending from Pima Butte to Sratuka. This area had an overlap of Piipaash and O’otham cultures. Early writings referred to Sacate as Sudaccson or Sutaquissón, a reference to the abundance of water in the area. Hueso Prado or Standing Bone was a Piipaash village located near the stagecoach stop of Maricopa Wells, west of Pima Butte or “M” mountain. In the 1870s, when water was being diverted upstream, the people moved. The people abandoned the village, moving to Gila Crossing, Sacate, Sacaton or Salt River. On behalf of all of us, the “guardians” of O’otham and Piipaash himdag were always seeking a better way of life.

It would be nice to begin a conversation with some of the elders you know and ask them about some of the villages names listed. It may trigger a memory of long ago. A couple of generations in the future, someone will ask where and what were the traditional villages on Gila River Indian Community. The answer may begin with, “Well, I remember a Baloney Town, Dog Town, and Beverly Hills…”

Other publications were used; Forced to Abandon Our Fields by David H. DeJong and Peoples of the Middle Gila by John P. Wilson.